History of China Camp

From Coast Miwok to Spaniards and Chinese immigrants, discover a diverse past

Prehistory to 1775

Coast Miwok Homeland

China Camp State Park occupies an area that was inhabited for thousands of years by the Coast Miwok people. The Miwok had dozens of small villages scattered throughout Marin and southern Sonoma Counties, including several settlements in the vicinity of China Camp. The Miwok had a subsistence lifestyle, hunting game such as deer and rabbits, harvesting acorns, fishing, and gathering clams, oysters, and other shellfish.

It’s estimated that several thousand Coast Miwok lived in the region when Spaniards arrived in 1775. Within a century, the Miwok were nearly wiped out. Today, there are still some Miwok scattered across the Bay Area, with the largest group at Graton Rancheria in Sonoma County.

1775 TO 1869

Spanish Settlers On A Mission

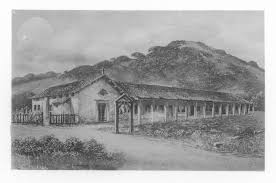

The Spanish first sailed their ship, the San Carlos, into San Francisco Bay in 1775. In 1817, Spaniards established Mission San Rafael Arcángel in the center of what’s now known as San Rafael, about 4 miles southwest of China Camp. Coast Miwok, as well as members of Pomo and Ohlone tribes, were soon converted to Catholicism and joined the mission, abandoning their former ways of life.

Shortly after Mexico gained independence from Spain in 1821, the old Spanish missions were secularized. The land was supposed to be returned to the Miwok. Instead, land was seized to enrich those with influence and power, and the Miwok got nothing.

The land was supposed to be returned to the Miwok. Instead, land was seized to enrich those with influence and power, and the Miwok got nothing.

1828 to 1853

An Irishman's Star Rises and Falls

Trade restrictions were eased under the new Mexican government. Early California grew rapidly, with Americans and Europeans flooding in to do trade with the booming number of pueblos and ranchos. Timothy Murphy, an Irishman who arrived in 1828, became the administrator at the former San Rafael Mission. Soon, he took on the title of alcalde, or mayor, of San Rafael.

Murphy’s star was rising. In 1844, Mexican governor Manuel Micheltorena granted Murphy, known as Don Timoteo Murphy in Spanish, a 21,679-acre land grant, called Rancho San Pedro, Santa Margarita y las Gallinas. Included was much of the area now designated as China Camp State Park.

Don Timoteo’s light didn’t shine quite so brightly once America took over California in 1846. By 1849, he had lost most of his land to swindlers. Murphy died in 1853 of a burst appendix. His once extensive empire was divided up and sold to cover his debts.

1869 TO 1855

McNear Empire Takes Over San Pedro Peninsula

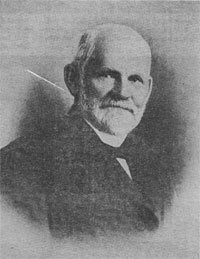

In 1869, a large portion of Timothy Murphy’s rancho was purchased by John A. McNear (pictured here) and his brother George. The McNear brothers were businessmen and landowners in Sonoma County, where they had made their fortune. They established a large dairy ranch that covered more than 2,500 acres, including five miles of waterfront along San Pablo Bay.

The McNears’ original plans included a shipping terminal and a railroad line that connected to San Rafael, but they lost their financial backing after the 1906 earthquake and fire in San Francisco. The McNears did succeed in establishing a number of business enterprises on the former ranch, including a quarry and a brickyard.

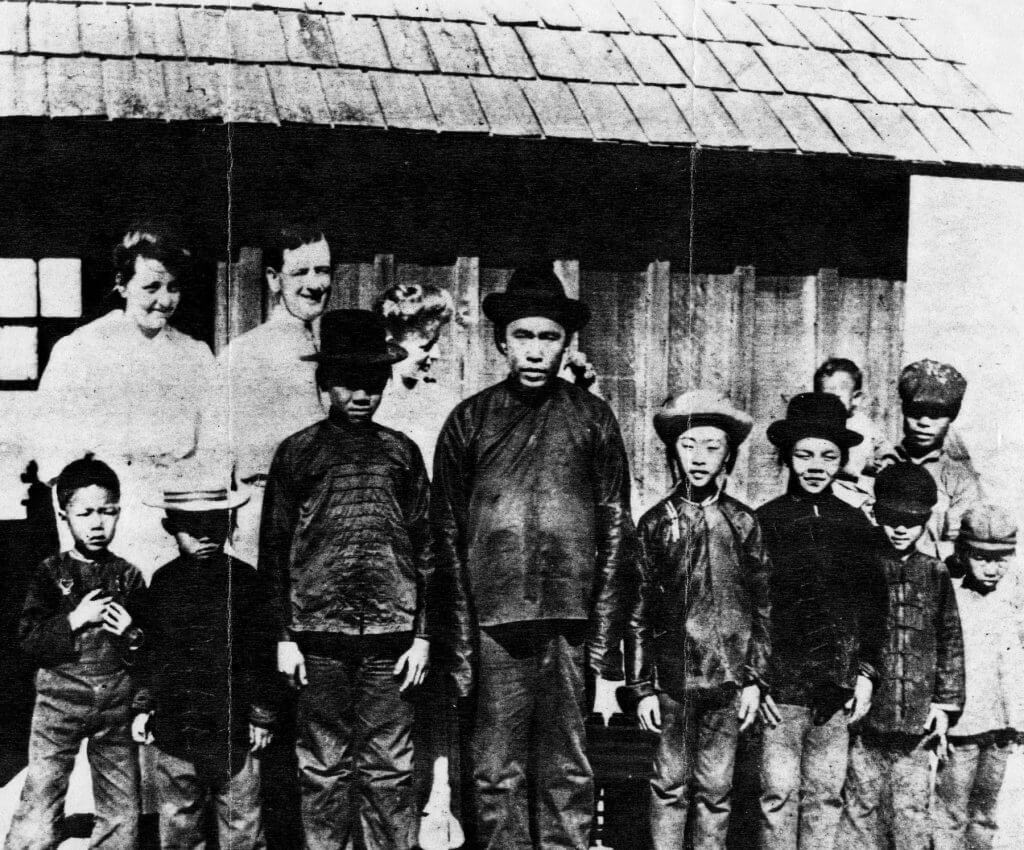

Chinese immigrants, who had been in Marin County as early as 1855, found work as laborers at the McNear Ranch. They supplemented their income by fishing for shrimp along the shores of San Pablo Bay, setting up temporary camps around the McNear property.

More than three million pounds of shrimp were harvested from San Pablo Bay each year throughout the late 1800s and into the early 20th century.

1855 TO 1882

Chinese Immigrants Find A Home

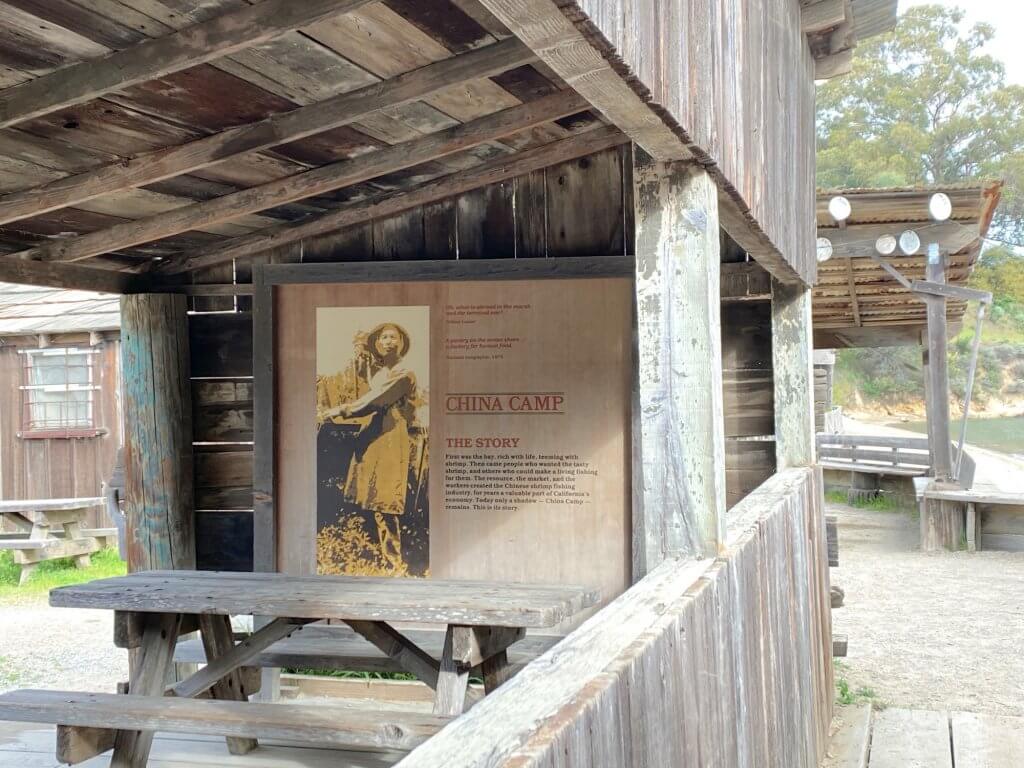

Though there were once more than two dozen shrimping camps like China Camp located around San Francisco and San Pablo Bays, this state park preserves the only one as a historic site, providing a unique opportunity to learn more about this important period.

China Camp’s location on the shores of San Pablo Bay were ideally suited for shrimping. It provided perfect conditions for a shrimping camp: close proximity to the fishing beds, adequate space for processing facilities on land, and a nearby grassy hillsides for drying shrimp.

While some of the shrimp was sold to local restaurants, most of the catch was dried and prepared for export to China. The sheer amount was staggering, with more than three million pounds of shrimp was harvested from San Pablo Bay each year throughout the late 1800s and into the early 20th century.

China Camp Village reached the height of its prosperity in the 1880s, with almost 500 residents. There were several small streets lined with wooden buildings, including general stores, a marine supply store, a barber shop, shrimp drying and grinding sheds, and numerous residences.

1882 TO 1905

Anti-Chinese Sentiment And Harsh New Laws

China Camp Village grew considerably in the 1870s and 1880s, at a time when vicious anti-Chinese sentiment was sweeping California. The economic recession of 1877 made scapegoats out of Chinese laborers, who were viewed as foreigners taking jobs away from Americans.

Labor union leaders took advantage of this sentiment and rallied unemployed workers under the cry of “the Chinese must go!” In the midst of this atmosphere, many Chinese were drawn to the remote location of China Camp, where they could carry out self-sustaining lives away from the persecution and discrimination of the cities.

With the passage of the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1882, immigration from China was severely limited, the first time in American history that a specific nationality was prohibited from immigrating to the United States.

Over the next few decades, additional discriminatory laws were passed against the Chinese, making life difficult for the fishermen of China Camp Village. In 1905 the export of shrimp was outlawed, striking a severe blow to the China Camp economy. In 1911, the use of the traditional bag nets favored by the Chinese was prohibited. As a result of these laws, the population of China Camp Village declined until almost all residents were gone.

Many Chinese were drawn to the remote location of China Camp, where they could carry out self-sustaining lives away from the persecution and discrimination of the cities.

1905 TO 1955

Quan Family Legacy

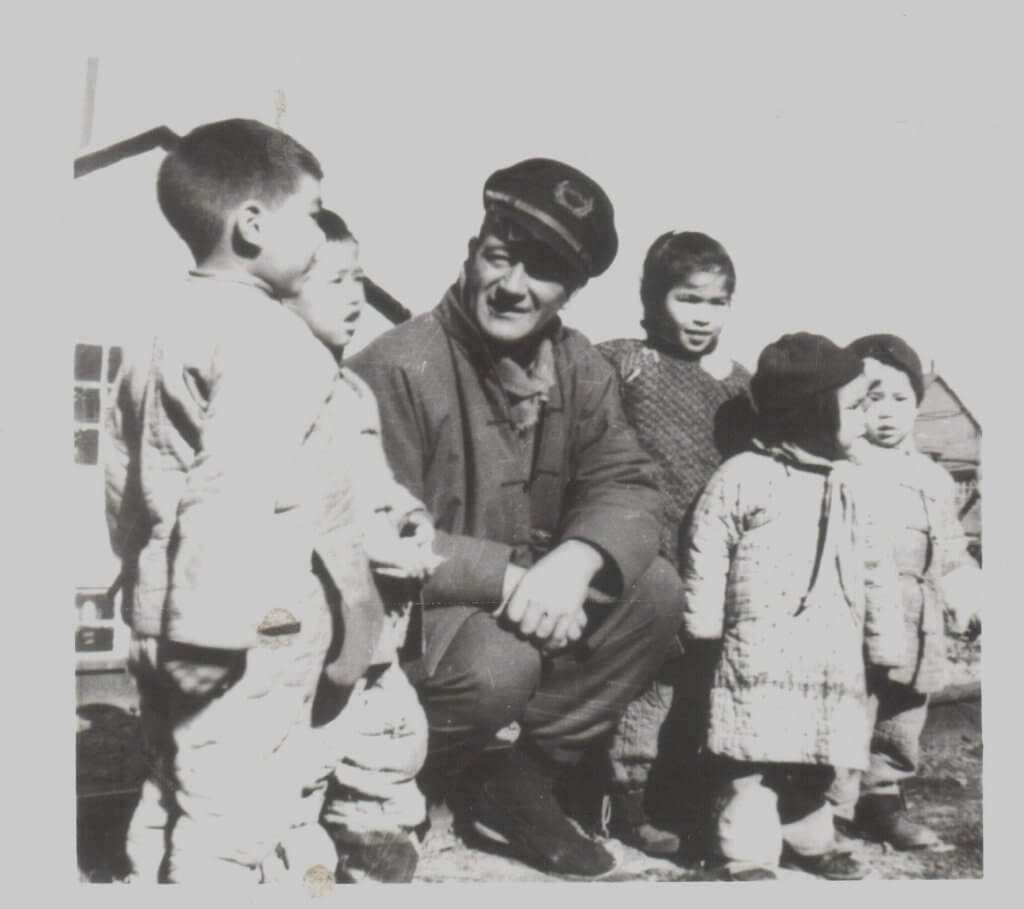

Among the early residents of China Camp Village was Quan Hung Quock, who moved here from San Francisco’s Chinatown in the late 1800s. Quan Hung Quock built a general store here in 1895 and raised a family. His grandson, Frank Quan, was the last original shrimp fisherman to live at China Camp Village, staying in his cabin at the park until his death at age 90 in 2016.

The cafe was a vibrant part of the Quan legacy. With its beachfront location, and delicious shrimp cocktail on the low-key menu, the eatery was a popular destination for locals. Unfortunately, the local shrimp fishery has been almost completely depleted in recent years, as water diversion and pollution have compromised the health of the once vibrant ecosystem.

1955

Make Way For Movie Stars

China Camp Village was the scene of filming of the movie Blood Alley in 1955. John Wayne and Lauren Bacall starred in this classic Cold War-era adventure, in which China Camp Village played the role of a small village in China.

The story revolves around a missionary’s daughter named Cathy Grainger, played by Bacall, who is attempting to help an entire village escape from the Communists by fleeing to Hong Kong. The Bacall character enlists the help of reluctant Merchant Marine Captain Tom Wilder (Wayne), who pilots a decaying old ferryboat down a 300-mile stretch of Southern China coast known as “Blood Alley.”

Viewed through a modern lens, Blood Alley is a reflection of Cold War hysteria, as well as Hollywood’s historically inaccurate portrayal of the Chinese. Many of the key Chinese roles in the movie are played by Caucasian actors, and the dialogue is shockingly jingoistic from a contemporary point of view. That said, the movie did add a dose of glitz and glamour to China Camp, and many of the residents appeared as extras in the film.

Scenes of China Camp make for entertaining viewing, with a large fabricated castle on the hillside above the village. Rat Rock has a prominent function in the plot of the movie, serving as a point where the villagers lay a trap for Communist gunboats that pursue the fleeing ferryboat.

The movie added a dose of glitz and glamour to China Camp, and many of the residents appeared as extras in the film.

1960 TO 1976

Development Looms But Parkland Prevails

Over the years, China Camp had become a popular locale for relaxing and enjoying nature and the bay front, especially at China Camp Village. By the 1960s, most of the San Pedro Peninsula was owned by developer Chinn Ho and his New York California Industrial Corporation. Gulf Oil Company had its eye on the property, after having lost its bid to develop the Marin Headlands in 1972. Gulf Oil had a massive development in mind for the area, with large commercial areas, light industry, high-rise condos, and an estimated population of 30,000.

Homeowners in the nearby Peacock Gap residential area started to hear rumors about the proposed development and took action. Louise Kanter Lipsey, Tina Ferris, and Sandy Hanson formed Save San Pedro Peninsula in 1972, a group whose objectives were, among others, “to preserve as open space the ecologically unique and environmentally significant land of the San Pedro Peninsula.” They enlisted the help of local environmental and conservation groups, particularly the Marin Conservation League. With the help of Robert Young from the League, an Environmental Impact Report was drawn up, which was followed by a proposal to establish China Camp Shoreline Park.

1976 TO 1979

The Birth of China Camp State Park

The efforts of Save San Pedro Peninsula paid off. In 1976, the California State Park Foundation (CSPF) bought most of the holdings of the New York California Industrial Corporation for $2,310,000. The purchase included 1,640 acres of what had long ago been the McNear Ranch, along with much of San Pedro Peninsula. In addition, the 36-acre site of China Camp Village was donated by developer Chinn Ho, who wanted the area to be preserved as a memorial to Chinese-American history.

Later that year, the State of California, on behalf of the Department of Parks & Recreation, purchased the property, and China Camp State Park was established in 1977. The park’s general plan, drafted in 1979, included special allowances for Frank Quan (pictured here), so that he could “continue his life-long tenancy in the area.”

1979 TO 2011

State Budget Woes Threaten Park Closure

For nearly three decades, China Camp was managed solely by the State of California. But then the state’s economy crashed in 2008, forcing deep funding cuts for California State Parks. Former Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger tried to shut down 220 of California’s 278 state parks, including China Camp. His proposal was ultimately scaled back, settling instead for reduced maintenance, less administrative staff, and shorter operating hours at most parks.

A ballot initiative, Proposition 21, was put before California voters in 2010. Its goal: to ensure that state parks would have a steady and reliable source of funding. Financing would come from an $18 increase in vehicle license fees. Unfortunately, this progressive and far-sighted proposal didn’t pass.

Budget shortfalls continued. By now, Jerry Brown had been elected Governor. In 2011, Brown proposed a budget requiring permanent closure of 70 state parks, including China Camp. Locals again rose up to defend the park, and to come up with a solution that would avert closure and guarantee the financial viability of the park.

2011 TO PRESENT

The Future Looks Bright With Friends of China Camp

After months of fundraising, Friends of China Camp raised enough money and support to take over operations at the park. In 2012, just days after assuming responsibility, the group learned that the California Department of Parks and Recreation had stashed away more than $50 million that could be used for state parks. Then-State Assemblyman (and now U.S. Congressman) Jared Huffman froze the closures and developed a plan to match funds and volunteer hours to support local operating agreements, such as that at China Camp.

China Camp State Park is no longer threatened with closure, and has even expanded services. Back Ranch Meadows Campground along with the picnic sites at Buckeye Point and Weber Point are open seven days a week, and can be reserved through ReserveCalifornia. A well-maintained muti-use trail network leads to marshlands, meadows, forests, and vistas. The village area, including the cafe, still draw locals and beyond for a fun day at the beach. Volunteer activities abound, as do interpretive programs and special events honoring China Camp’s unique place in San Francisco Bay Area history.

China Camp State Park

New map highlights California’s early Chinese history

Discover sites in Northern California, including China Camp, where Chinese settlers had a significant historical presence.

Find out more about China Camp.